Words by Raven Rodriguez

(10 min. read)

In the blazing aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, corporate America scrambled to perform its conscience and declare solidarity with racial justice. Press releases poured in like rehearsed apologies. DEI departments appeared overnight, tasked not with structural repair but image management. Ben & Jerry’s, helmed by white executives with an eye for optics, declared war on white supremacy. And suddenly, across the marketplace, solidarity became a thing to be branded, boxed, and sold.

Ralph Lauren, a name etched into the fabric of aspirational whiteness and steeped in the mythology of old money and American aristocracy, took a more tailored approach. It partnered with two historically Black colleges, Morehouse and Spelman, to produce a commemorative clothing line. A capsule echoing the crisp lines of varsity jackets, the elegance of Spelman’s traditions, and the gravitas of Morehouse’s legacy. Priced far beyond the reach of millions of Black Americans. On the surface, it suggested evolution: a nod to a new, more inclusive American story. But this is a story told in fragments. It demands forgetting who Ralph Lauren has always been and for whom the American dream was stitched.

“Polo Ralph Lauren for Oak Bluffs” takes us to the beautifully manicured lawns of Martha’s Vineyard. It is billed as a tribute to the Black enclave of Oak Bluffs, a haven for Black elites since the late 19th century. The capsule blends coastal leisure with HBCU pride and collegiate tailoring. The campaign imagery evokes the warmth of a multigenerational family reunion. Homage, we are told, to heritage, community, and belonging. But beneath the nostalgia lies something far more complicated.

Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard was never just a summer retreat. It was a radical act of Black self-preservation, a claiming of space in a world that was never meant for us. There, Black families with enough wealth and status to buy property in a predominantly white vacation haven built lives of quiet rebellion, carving beauty and safety into the margins of white dominance. Long before Ralph Lauren’s name adorned department stores and magazine pages, Black families in Oak Bluffs were already living the elegy of arrival. Their linen, their seersucker, their soft pastels were not fashion statements but declarations: We are still here. We are worthy. We belong.

The capsule is paired with a 22-minute film, A Portrait of the American Dream: Oak Bluffs, and partnerships with nonprofits, all wrapped in the language of cultural preservation. But preservation under capitalism is not memory, it’s marketing. What gets remembered is what can be sold. Oak Bluffs, like so many Black enclaves, was born from exclusion, not inclusion. Its beauty was not gifted; it was built, brick by brick, in defiance of the world outside its borders. The wealth seen there was not merely earned; it was wrestled from a country that never intended for us to rest easy. To romanticize that victory without naming the forces that made it necessary is to admire the ember and ignore the blaze.

Ralph Lauren’s depiction of Blackness, no matter how artful, no matter how archival, is still framed by the same economic machinery that once rendered us invisible and now monetizes our presence as proof of progress. Families in Oak Bluffs adorned themselves in beautiful clothing not to imitate whiteness, but to resist invisibility. They signaled belonging through clothing long before a marketing team decided their Blackness was profitable. The irony, of course, is that what Ralph Lauren would one day brand as the American dream was already being lived. Quietly, defiantly, by Black families who deep down knew the truth: clothing would never protect them, it would only give them room to breathe.

The capsule is not about inclusion. It’s a rehearsal of old myths. Myths that tell us safety is a luxury, that elegance is earned, that belonging comes stitched inside a linen blazer.

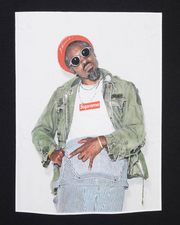

This was not unique to Ralph Lauren. It was part of a larger pattern of Black consumers using fashion as a form of assertion, an attempt to claim belonging, safety, and success in spaces that had historically been hostile to them. By the late 1980s, Polo had become iconic in urban Black communities. A subculture emerged where Black youth repurposed the brand’s elite-coded clothing into a badge of defiance, style, and cultural remixing. From the Wu-Tang Clan’s iconic use of the Polo Snow Beach jacket, Kanye West’s reclaiming of the Pink Polo as a symbol of confidence and creativity, to Young Dro’s collection becoming both aesthetic and anthem, the brand has been deeply embedded in Black identity and resistance. Though these movements were not connected to Oak Bluffs, they serve as a crucial reminder that Black people have long engaged with Ralph Lauren in layered and contradictory ways.

Throughout the accompanying film, one hears the language of distance: a better life, a safer life, a place where our parents didn’t worry about us. And yet what is this better life, if not a quiet refuge from the fire that still burns? What do we make of a freedom so precious, so rare, that only the fortunate few can touch it? This is not a celebration of Black safety, it’s a eulogy for its scarcity. And still we celebrate it. We dedicate documentaries and capsules not to the transformation of Black life, but to the preservation of its most exceptional.

One interviewee says, “We are striving to participate in the American Dream.” But that is the lie at the heart of Black elitism. The belief that freedom lies in ownership, that safety comes not from collective liberation but from individual insulation. It is not a dream of abolition, but of adjacency. The beauty in this film is not a call to end Black suffering, but a well-tailored plea to suffer less. An elegant bid for a seat next to those already spared.

The capsule is not about inclusion. It’s a rehearsal of old myths. Myths that tell us safety is a luxury, that elegance is earned, that belonging comes stitched inside a linen blazer. It does not interrogate why safety was so rare to begin with, why Black children needed islands to roam freely. It does not ask why sanctuary remains a private luxury, instead of a public right. This is not homage. It’s a brand’s performance of progress, designed for a white gaze still invested in the myth of its own benevolence. Today, that same elite image is packaged and sold as “representation,” when it’s always been about assimilation and proximity, not to liberation, but to the American Dream as imagined through whiteness. The collection symbolizes what Black culture can become when confined within corporate America’s limits, not what it could be if freed from the grip of capitalism.

This is the “brand ambassador” syndrome, profiting from Black culture while leaving intact the very structures that oppress Black lives.

In 2021, Jeff Miller, a senior executive of the NFL, was caught on record suggesting that Black players possess “less intellectual capacity” to suffer concussions like their white counterparts. A scientifically unfounded claim that exposes the league’s dehumanization of Black athletes and the racialized calculus embedded in their approach to safety. This was not a misstep, nor a relic of ignorance. It was a revelation, a glimpse into the brutal architecture of the league’s logic. A reminder that, beneath all the talk of equity and safety, Black bodies are still seen as tools to be used, not lives to be protected. This is the same league that, just months ago, sanctioned the most televised Crip Walk in history. Kendrick Lamar’s halftime performance at the Super Bowl was a spectacle of Black choreography, and beneath the blinding lights of patriotism, rebellion was rehearsed, defanged, and made safe for American consumption.

On that very same field, not far from where Kendrick performed, Zul-Qarnain Kwame Nantambu, a 41-year-old Black man from New Orleans, was arrested for waving a flag in support of the Sudanese and Palestinian people. An injustice meant to remind us who gets to dance and who dares not speak.

But none of this is unique to the NFL. It is the pattern of a nation that accepts Blackness only when it is sanitized and profitable. Where the performance of freedom is favored over its actualization. And Ralph Lauren’s HBCU and Oak Bluffs collections, wrapped in American iconography, are no different. This is the paradox of Black visibility under capitalism: a hunger for Blackness, so long as it never threatens the structure itself. These pageants are not revolutionary. They do not overturn the material realities of capitalism or racism. Resistance that challenges empire requires revolutionary politics, mass organization, and the rejection of settler colonialism and white supremacy in every form. Yet so many remain invested in narratives that celebrate Black cultural symbols without demanding systemic change.

This is the “brand ambassador” syndrome, profiting from Black culture while leaving intact the very structures that oppress Black lives. The conversations around this collection in online spaces reveal a stark absence of the intellectual tradition of Black critique on elitism and co-optation. Black scholars and authors such as Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor have long warned about the dangers posed by elites who become complicit in maintaining oppressive systems. For decades, these critical frameworks have existed. Yet, today, many Black people voicing legitimate critiques of the capsule are met with anti-Black hostility and surface-level dismissal that reminds us exactly why critical thinking matters, especially when legacy and nostalgia are used as shields to deflect important questions about power and exclusion. To ignore these voices is to ignore the structural dynamics that allow brands to market Black culture in ways that are palatable to whiteness while leaving systemic exploitation intact.

This erasure of critical thought highlights how, in the internet age, discourse is often fragmented and lacks historical depth. Instead of building on the foundational work of Black intellectuals who have mapped the intersections of race, class, and capitalism, online discourse becomes bogged down by performative loyalty to brands or defensive backlash. The sanitized nostalgia for Black revolutionary imagery, whether in fashion, music, or political rhetoric, is part of the problem. As capitalism co-opts rebellion to sustain itself, America continues to turn radical images into commodities.

Even more troubling is the silencing of critique itself. Some insist the capsule is not meant to provoke, not meant to disrupt, but to honor. A gesture of reverence toward Black communities like Oak Bluffs. They point to the involvement of Black designers as proof of intention, as if proximity to Blackness could shield a project from critique. But corporate structures like Ralph Lauren’s retain ultimate control over brand messaging, product pricing, and the politics of inclusion and exclusion. The design process may be Black-led, but the conditions of production, distribution, and consumption remain firmly embedded in capitalist logics that privilege exclusivity, commodification, and profit over community.

This is not a rejection of Oak Bluffs, nor an indictment of Black memory. It is a call to honor that memory with the full truth, not the designer version.

If we are to speak honestly about Black liberation, then we must stop mistaking legacy for revolution, nostalgia for resistance, and representation for freedom. We must refuse the lie that only the exceptional among us are worthy of celebration. Our ancestors did not suffer, so we might one day wear $1,000 linen blazers on manicured lawns. They did not sacrifice; they were sacrificed. And to fold their unspeakable grief into some myth of eventual inclusion in the American Dream is not remembrance; it is erasure. We call ourselves Black because the names of our origins were stolen, lost to the Atlantic. We have been taught to chase an empire that made itself rich from our chains.

For some of us, this obsession with the American Dream is a kind of capitalist Stockholm Syndrome, a longing to own what has owned us. Black excellence, too, has been contorted. It is no longer measured by how it frees us, but by how loudly it disrupts white comfort, how gracefully it performs under the weight of empire. But freedom is not found in performance. It is found in refusal—the refusal to aspire to what was built to crush us. “We are our ancestors’ wildest dreams” is a beautiful phrase, but it implies that the measure of our progress lies in our capacity to transcend, to rise, to achieve, so long as that achievement is legible to America. The mythology of Black exceptionalism cannot save us.

This is not a rejection of Oak Bluffs, nor an indictment of Black memory. It is a call to honor that memory with the full truth, not the designer version. Oak Bluffs was not built out of ease or abundance. It was carved from necessity, born of redlining, exclusion, and the quiet violence of generational dispossession. To summon these places without naming the conditions that created them, without grappling with the ongoing theft that still defines so much of Black life in this country, is wrong. It is the turning of violence into style, an aesthetic of survival sold back to us by the very machine that made it necessary.

This is a call to think critically about what it means when America begins to sell us back our reflection, wrapped in gold trim, curated just enough to feel familiar, but never radical enough to disrupt. The question has never been whether Black people deserve celebration. The question is: Who gets to define the terms? Who profits from the performance? And on America’s grandest stage, who gets to dance — and who is arrested for daring to speak? As the country descends further into fascism, and as Black leaders and cultural icons become brand ambassadors for a system that exploits them, we must remember: no performance, no fashion, no curated “portrait of the American dream” will substitute for the work of actual revolution.

To honor heritage, community, and belonging is to tell the truth: We were there before the myth, before the market, before gilded visions of Black opulence were pressed into coffee table books and sold back to us as revelation. We built beauty in the margins, not because we were invited, but because we refused to disappear. Ralph Lauren arrived late.

So let me be clear: We are the blueprint. Not reaching for luxury, just reaching for each other. And we are exquisite, with and without notice.

*All photos from Polo Ralph Lauren for Oak Bluffs.*